- Home

- Chris Petit

The Butchers of Berlin

The Butchers of Berlin Read online

Also by Chris Petit

Robinson

The Psalm Killer

Back from the Dead

The Hard Shoulder

The Human Pool

The Passenger

First published in Great Britain by Simon & Schuster UK Ltd, 2016

A CBS company

Copyright © Chris Petit, 2016

This book is copyright under the Berne Convention.

No reproduction without permission.

® and © 1997 Simon & Schuster, Inc. All rights reserved.

The right of Chris Petit to be identified as author of this work has been asserted in accordance with sections 77 and 78 of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988.

Simon & Schuster UK Ltd

1st Floor

222 Gray’s Inn Road

London WC1X 8HB

www.simonandschuster.co.uk

Simon & Schuster Australia, Sydney

Simon & Schuster India, New Delhi

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

Hardback ISBN: 978-1-47114-340-3

Trade Paperback ISBN: 978-1-47114-341-0

eBook ISBN: 978-1-47114-342-7

This book is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places and incidents are either a product of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual people living or dead, events or locales is entirely coincidental.

Typeset in the UK by Hewer Text UK Ltd, Edinburgh

Printed and bound in Great Britain by CPI Group (UK) Ltd, Croydon, CR0 4YY

Simon & Schuster UK Ltd are committed to sourcing paper that is made from wood grown in sustainable forests and supports the Forest Stewardship Council, the leading international forest certification organisation. Our books displaying the FSC logo are printed on FSC certified paper.

To Anna and Iain

Contents

PART ONE

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

PART TWO

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

54

55

56

57

Afterword

PART ONE

1

It was still dark as the old man dressed. The light would not come for another hour. Socks and suspenders. Trousers and braces. The underpants of which he was so ashamed, dish-wash grey and stained, for lack of soap, so threadbare they were in holes. His shoes, once good, barely held together and leaked at the slightest provocation. They smelled of the detergent used to wash the slaughterhouse floor. The medal deserved a collar, he thought. He had no cufflinks either and made do with rolled sleeves. The suit still had its waistcoat, which he wore for the little extra warmth it afforded, usually under his one sweater, which he discarded that morning, wanting to look his best. He took his overcoat, hat and scarf, which hung on the back of the door. As an afterthought, he folded his pyjamas and placed them under the pillow. He wanted the gesture to provoke some regret or nostalgia but felt nothing.

The pistol was an old Mauser C96. He appreciated the aesthetics of its distinctive box magazine in front of the trigger, the long elegant barrel and comfort of the wooden handle. His last companion of choice. His hands were cold but he would not wear gloves. He passed through the apartment, careful not to disturb the others because he wished to leave unobserved. He closed the door softly behind him, stood at the top of the stairs and stared into the descending gloom.

The block warden was slow to arrive. He was a short man with a childish face and the insolent, spoiled look of minor authority. He didn’t see the pistol in the old man’s hand until he raised his arm. He gave a small yelp of surprise, followed by his characteristically unpleasant laugh, which he never had time to finish. He was in the middle of putting on his coat, with his mouth open, when the bullet entered his head, through the eye, at which the old man had been aiming. His head snapped back from the force. Blood and bone hit the wall, followed by the bullet. He slumped back and slid down, his blood a dark smear on dirty paintwork. The remaining eye fluttered, almost coquettishly, as he hit the floor sitting, paused and rolled over.

In the booming echo of the shot the old man thought he heard footsteps stop on the stairs. Female. He knew whose and regretted he could do nothing about that; perhaps she was his angel of death after all. At least he was her avenger.

The old man turned the gun on himself, grasped the barrel in his left hand to hold it steady and pulled the trigger. The bullet travelled upwards through the unresisting flesh of his chin and tongue, missing his false teeth, into the soft palate of his mouth, passing the nasal passage, to penetrate the brain where it lodged, causing none of the messy damage of the first shot. Such a neat, clean death; the old man was gone before he hit the ground, doing more tidily for himself than his victim, who jerked and twitched like a dog in a dream.

The young woman was still standing petrified when the second shot fired. A voice in her head told her not even to think and get out. She ran with her hand over her mouth until she reached outside and spewed in the courtyard as the door banged behind her, barely stopping before she carried on running.

2

August Schlegel woke up in a prison cell with no recollection of how he had got there. Everything swam unpleasantly. He wondered if he were still drunk. Like a man contemplating white space on a map, he thought, ‘My name is August Schlegel and the street where I live is the same as my first name, in the former Jewish quarter.’ He opened one eye. Had they thrown him in the drunk tank? There were many things he disliked about himself, starting with his name. He was only twenty-five but his hair had gone quite white, which he also disliked, as he did the way it sat on top of his open, ordinary face.

The air stank of stale drink. He had a memory of throwing up during the party. The party. There had been speeches. A big room full of boozed-up men. A group of the oldest and toughest had decided to make him the butt of their lurid and preposterous tales. Stoffel claimed to have dressed as a woman for the S-Bahn murders, to act as bait. The idea was beyond imagination. Stoffel was bull-necked with a boxer’s nose and a tobacco-stained moustache, which he claimed to have shaved off for his drag act. Tears of mirth ran down everyone’s cheeks.

They were all reeling drunk by the end. He remembered wondering if he would end up spending the night in the cells again; it seemed to be happening more often. He recalled standing swaying, trying to read his watch, and someone saying, ‘Ach! After eleven. Too late to go home. Everyone downstairs!’

Sleeping it off in the cells was standard police practice.

He must have dozed off. The next thing he knew, he was being poked awake. The reek of brutal aftershave told Schlegel it wasn’t just a bad dream. He ran his furred and distended tongue around his teeth and tasted a ho

rrible residue. He could feel his swollen liver.

‘You’ll do,’ said Stoffel, continuing to poke him.

‘What for?’

‘A homicide.’

Schlegel couldn’t find his hat and one glove was lost. His jacket and coat were wadded up under the bunk. At least the big leather waistcoat was still there. He kept repeating under his breath: I am not homicide. On the rare occasions Schlegel found himself drinking with the likes of Stoffel – at leaving parties, and there were plenty of those – he had a warning list in his head of subjects never to mention, however drunk. He hoped the image he had of himself regaling them hadn’t happened. Stoffel’s crowd were always laughing at things not in the slightest funny until someone said something really funny, when they made a point of not laughing at all.

He arrived in the garage hatless, his ungloved hand stuffed in his pocket. Stoffel was sitting in an Opel with the engine running. The garage was bitterly cold and it was no warmer in the car, whose heater didn’t work.

‘I am not homicide, you know,’ he said to Stoffel.

‘The rest are busy.’

Busy sleeping it off, he thought sourly. Where was his hat? It was a good one.

There was a hole in the floor of the car and a chilly draught blew up his legs. He suspected Stoffel wore newspaper under his vest from the way he rustled. There was much discussion about what gave the best insulation. Stoffel smoked a foul cheroot. He was a wet smoker. Schlegel was aware of not having cleaned his teeth, not that it mattered. Nearly everyone’s breath reeked these days. He tasted last night’s alcohol. No shortage there. Outside it began to spit. To stop from feeling sick, he concentrated on the grinding of the useless wipers and the smeared vision through the greasy windscreen.

A lot of official traffic was on the roads. Trams were crammed with commuters. Those banned from public transport trudged past with their heads down. Another grubby dawn, another working Saturday and another of those filthy colourless days found only in Berlin in winter, in the year of our Lord nineteen hundred and forty-three.

A roadblock was set up where the street had been sealed off. They were in a run-down working-class part of Wilmersdorf. Schlegel saw soldiers on standby, their scuttle helmets silhouetted in the drizzle. There were a lot of ordinary policemen too and plainclothes, as well as special Jewish marshals with armbands.

The man they were referred to wore the usual unofficial uniform of snap-brim fedora and leather trench coat. He gave them a peremptory look and said, ‘Gersten.’

Gersten’s hair was worn unusually long over the collar. Schlegel remained preoccupied with his hangover as they were led through an arch into a deep courtyard surrounded by dilapidated barracks-like blocks with crumbling brickwork, dark with soot.

‘Two Jews,’ said Gersten. He pointed to a block entrance.

‘You drag me out of bed for a couple of Jews!’ protested Stoffel.

‘Today the Jews are all busy getting arrested. We go in at full daylight, so you have five minutes to sort them out.’

Stoffel, still grumbling, said to Schlegel, ‘You tell me what happened. Consider it part of your education.’

Stoffel was already nipping from a hip flask.

They were in a ground-floor corridor that ran from front to back, outside the block warden’s quarters. The staircase took up most of the space. The hall stank of cordite. One man had been shot while putting on his coat and had fallen awkwardly. The eye was a gaping hole. The other by comparison appeared formally arranged, so neat he could have been laid out by an undertaker.

Schlegel passed Stoffel the pistol using his gloved hand. Stoffel looked at the weapon in appreciation.

Schlegel said, ‘The old man shot himself after shooting the other man. There may have been a witness who ran away.’

‘We’re not looking to complicate this.’

‘I stepped over a puddle of vomit by the door.’

Stoffel inspected the soles of his shoes, yawned ostentatiously and went outside. Schlegel followed. The yard was now surrounded by troops with submachine guns and attack dogs straining their leashes. He had heard nothing of their arrival.

Gersten beckoned them over. Stoffel insisted that Jews were not the business of the criminal police. Gersten ignored him and said Stoffel still needed certification of death.

‘Get the bodies out here in the meantime. They’re in the way.’

Gersten nodded to an SS corporal with a bull whip, who blew a long blast on his whistle. A squadron of Jewish marshals ran in and fanned out towards the block entrances. The corporal cracked his whip and the dogs pulled on their leads, followed by the noise of doors being hammered on and kicked in, then banging and screaming and people being yelled at.

Schlegel was quite unprepared for such controlled fury. It pitched him back to that other time, which he had trained his mind to blank, during the waking hours at least.

A man upstairs yelled, ‘No packing. Get dressed and out!’

Stoffel was in no hurry to move the bodies by himself. He ordered a couple of marshals who were in the process of chasing out the first residents.

The men hesitated until Stoffel shouted, ‘Unless you want to join the rest in the yard.’

A middle-aged woman tried to press money into Schlegel’s hand, saying a terrible mistake had been made, her name should not be on the list. Schlegel looked at the pathetic amount and turned away. The woman moved on to Stoffel, who took the money and told her to wait outside. He asked her name and said he would have a word. The woman babbled her thanks.

‘Go along, before I change my mind,’ said Stoffel not unkindly, pocketing the money.

The sound of blows came from upstairs, followed by a sharp crack and glass being smashed.

‘Dead body!’ a voice shouted.

Schlegel thought perhaps the old man had been forewarned. As to where he had got the gun or why he’d shot the other man, he doubted anyone would care. Stoffel was smoking another of his foul-smelling cheroots. The tip, even wetter than the last, reminded Schlegel of a dog’s dick. A steady crowd pressed downstairs. Some whimpered. Others complained about pushing. It was like watching a river surge.

Someone fell on the stairs. People started to get trampled. Schlegel tried to restore order, aware of Stoffel’s sceptical gaze. The crowd seemed incapable of stopping. Schlegel was close to losing control of himself as he saw back to that flat horizon, marshland, huge summer mosquitoes, villages little more than a collection of hovels.

He pulled people up and shouted at others. A scream from under a pile of bodies seemed to act as a sign for the pushing to stop. Schlegel walked away, leaving them to sort themselves out. The air outside was absolutely still. It had stopped raining, not that it had done more than drizzle. His hands trembled in his coat pockets.

The corporal snapped his whip and ordered everyone to stop milling around. He separated the mostly elderly men. One who tried to point out his wife was screamed at. The crowd recoiled whenever the dogs showed their fangs.

The two bodies were now lying dumped in a corner by the bins, behind the rank of soldiers. The old man wasn’t looking so neat now. Schlegel knelt down and put his hand inside the man’s coat, like a pickpocket. The wallet he extracted was fake leather. The papers were stamped with a ‘J’. Schlegel noted the name, Metzler, and the number of his apartment upstairs. The other man had no papers.

The corporal kept cracking his whip like he was Buffalo Bill. Anyone showing indecision was kicked into line by the Jewish marshals. An ugly pudding of a woman with orange hair let out a wail and ran across the yard, arms jerking like a wind-up doll. At the bins she threw herself on the body of the other man. The courtyard was momentarily stilled except for the woman’s keening. The corporal stopped to look, then screamed at one of the civilians, ‘You! Cockroach! Eyes front!’

Gersten had a stick of lip salve, used surreptitiously to moisten his mouth. He came over and said to Schlegel, ‘The other man was the block warden, not Jewish, so it

is technically a homicide.’

The woman paused her wailing to shout, ‘We are German. I won’t have my man touched by a Jew doctor. We were here years before this riffraff!’

Even for Stoffel this was too much. He snapped, ‘What difference does it make? One dead man is the same as another.’

Gersten looked worried. ‘In fact, one Jew didn’t shoot another. She’s right. You’re going to have to get a proper doctor now.’

The block’s only telephone was in the hall of the warden’s apartment. Through the door to the living quarters Schlegel saw what looked like a comfortable set of confiscated furniture. The telephone was fixed to the wall, with a phone book underneath. He called a doctor and an ambulance. He then spoke to the Jewish Association and demanded a hearse.

When Schlegel went back outside the corporal was yelling, ‘Do as you are told or the dogs will have you for breakfast!’

The purpose of his aggression was only to create more terror. A small boy duly wet himself from fright and stood transfixed by the expanding puddle at his feet.

An elderly Jewish medic had been found to pronounce the old man dead. He stood to address Stoffel. ‘Take a look at the medal around his neck.’

Stoffel leaned in and whistled.

The doctor said, ‘An old soldier deserves more.’

The medal, on a ribbon, had been hidden by the man’s scarf: Iron Cross, first class. Not many of those, thought Schlegel.

The doctor said, ‘A man prepared to die for his country.’

Stoffel, not usually short of an answer, was silent.

The widow yelled, ‘Fucking Yids! You’ll get what’s coming!’

Stoffel ordered two policemen to get her out of the yard before she caused trouble, then told Schlegel to take a look at the old man’s apartment. His leg hurt, he said, and he didn’t fancy the climb.

Locks were broken on many of the doors. Schlegel couldn’t understand why the process had to be so destructive. He half-expected the building to take its revenge for being so violated, causing him to tumble downstairs and break his neck.

In the yard names were shouted. Abelman! Abendroth!

Mister Wolf

Mister Wolf The Passenger

The Passenger The Psalm Killer

The Psalm Killer The Human Pool

The Human Pool The Butchers of Berlin

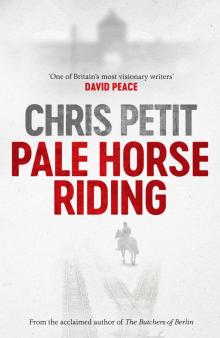

The Butchers of Berlin Pale Horse Riding

Pale Horse Riding